In celebration of Black History month, the Archives of the Big Bend is celebrating the history and accomplishments of the Black Seminole Scouts and their descendants who became residents of the Big Bend.

The origin of Black Seminoles began during the mid-18th century. Runaway slaves found haven amongst the Seminole Indians in Florida who were integrated as free Indian tribal members. Although they lived separately, Black Seminoles were perceived to be a major threat to the continued preservation of the American slavery system. They were a major cause in the First Seminole War in 1835 when US troops invaded Seminole lands in order to destroy Black Seminole Villages in an attempt to re-enslave them. After the Second Seminole War, they were moved to reservation lands in Oklahoma. In 1849 a substantial number moved to Mexico, where they are known as Mascogos, where they were employed by the Mexican government to guard the border.

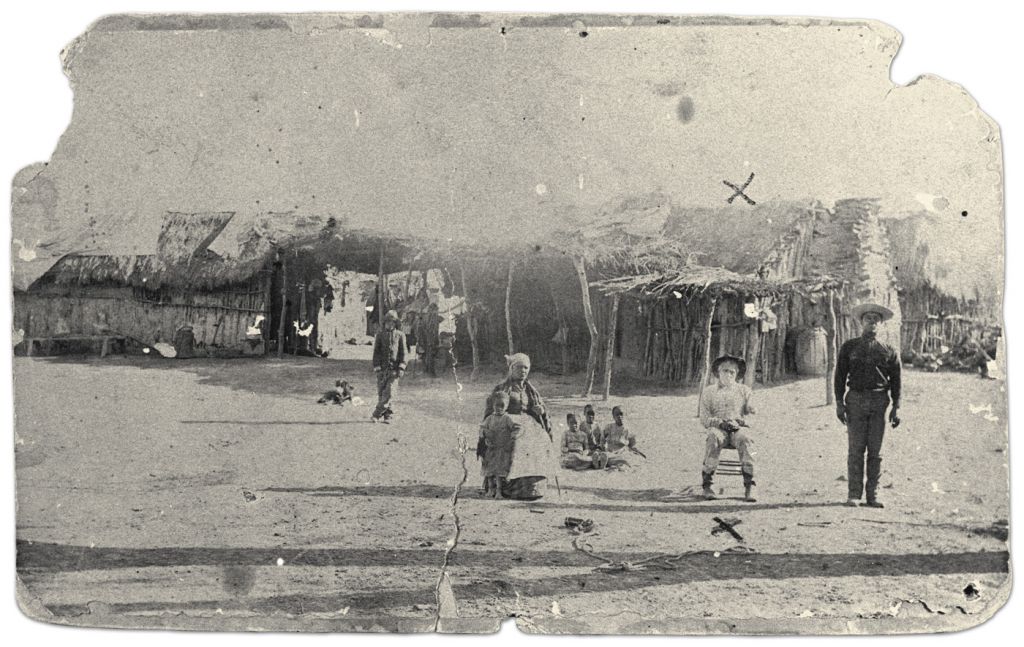

c. 1870-1880. Seminole Camp on Las Moras Creek, 2 1/2 – 3 miles below Brackettville. Families remained in camp when the men went to trail the Indians. The man on the right is Ben July, First Sergeant of the Seminole Scouts. His father and mother, Samson and Mary July are seated.

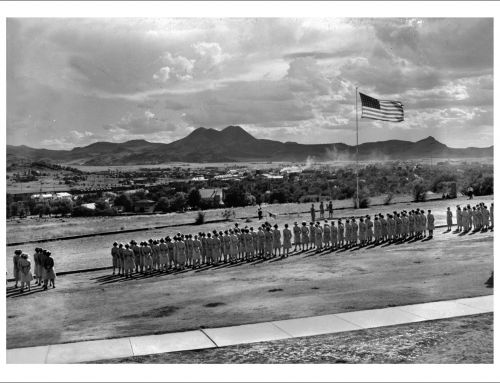

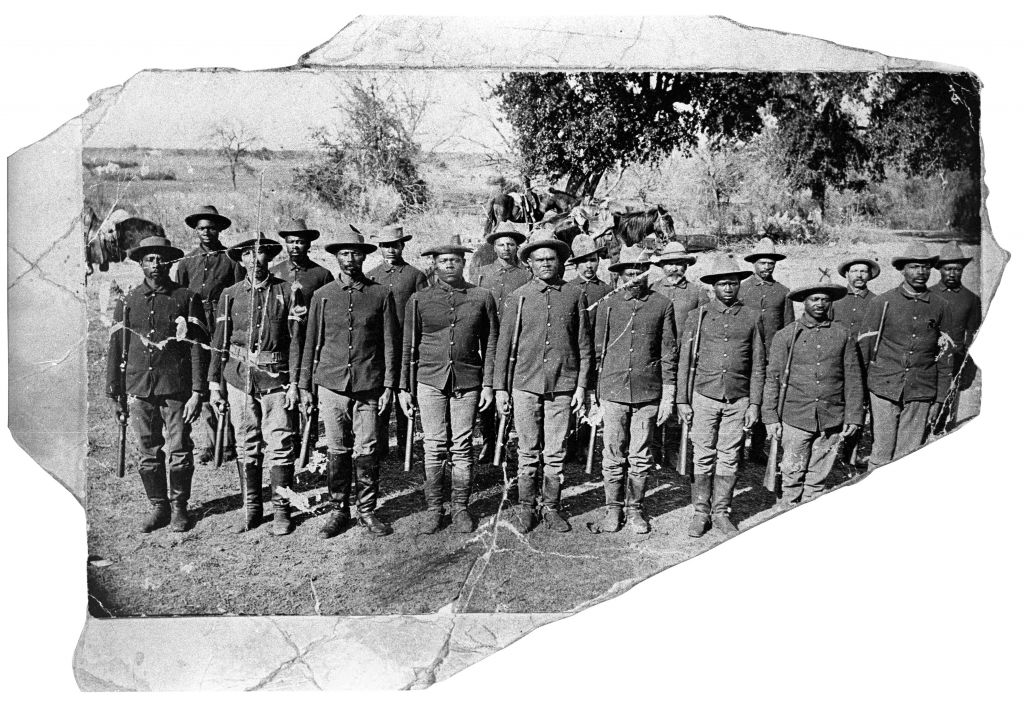

In 1870 the U.S. Army began negotiations to enlist Black Seminoles residing in Mexico as scouts to repel Apache and Comanche raids in Texas. In March 1873, Lieutenant John L. Bullis became commander of the Black Seminole Scouts. They brought their own horses and wore modified Seminole Indian dress. The unit participated in 26 official expeditions between 1873 and 1881. They were known for the Eagle’s Nest Crossing raid where they apprehended 75 Indians attempting to cross the Pecos River into Texas. Seminole Scouts also participated in the capture of the Apache leader Geronimo in 1886. Despite never numbering more than 150 servicemen, the Black Seminole Unit was one of the most decorated in the U.S. Army with four members winning the Congressional Medal of Honor. They accomplished all this with fewer supplies, equipment, and horses than other groups.

A Black Seminole regiment. Photo taken c. 1885.

By the late 1880s, Seminole Scouts were not used as often due to the “Indian Problem” being solved as the threats of raids became almost non-existent. They still functioned as a unit for another 18 years. By then, after struggling on how to classify the Scouts, the US Government ultimately decided to strip them of any benefits they may have gained by not classifying them as Seminole tribal members.

Possibly the most well known descendants of Black Seminole Indian Scouts in the Big Bend are the Payne Family of Marathon. Navidad (Nato) Mariscal, also known as “Isaac Payne” was captured by Comanches at a young age and fought as a Comanche against the US Army when he was apprehended in 1870. Nato liked how he was treated by the Army better, so he decided to join the Black Seminole Garrison in Fort Pena Colorado, which he helped build. Nato Payne received the Medal of Honor for his bravery. After 1879, when Nato served at Fort Davis, he met and married Antonia Payne, the widow of a Seminole Scout. He took her name and they became the Mariscal Payne family. They had four sons: Monroe, John, Bristas, and Alejandro before moving to a Seminole land grant near Nacimiento, Coahuila, Mexico.

Monroe Payne was born on May 15, 1872. He married Jesusita Vasquez and had seven children. He worked as a ranch hand for Lou Buttrill and the family lived near Bone Springs in southern Brewster County. In 1916, Monroe traveled to San Jose de las Piedras, Mexico to inspect his thirty head of cattle. On May 5, he was robbed and taken prisoner by Navidad Alvarez, Colonel of a group of Villista fighters. After being threatened with execution, Monroe was eventually rescued by U.S. soldiers under the command of Colonel Frederick Sibley and Major George T. Langhorne near Boquillas, Mexico. Monroe later sued the Mexican government for 50,565 dollars in damages related to his capture. He then moved his family to Marathon where he worked as a hauler.

Monroe and his daughter, Mary Payne Roach.

Monroe and his wife, Jesusita Payne.

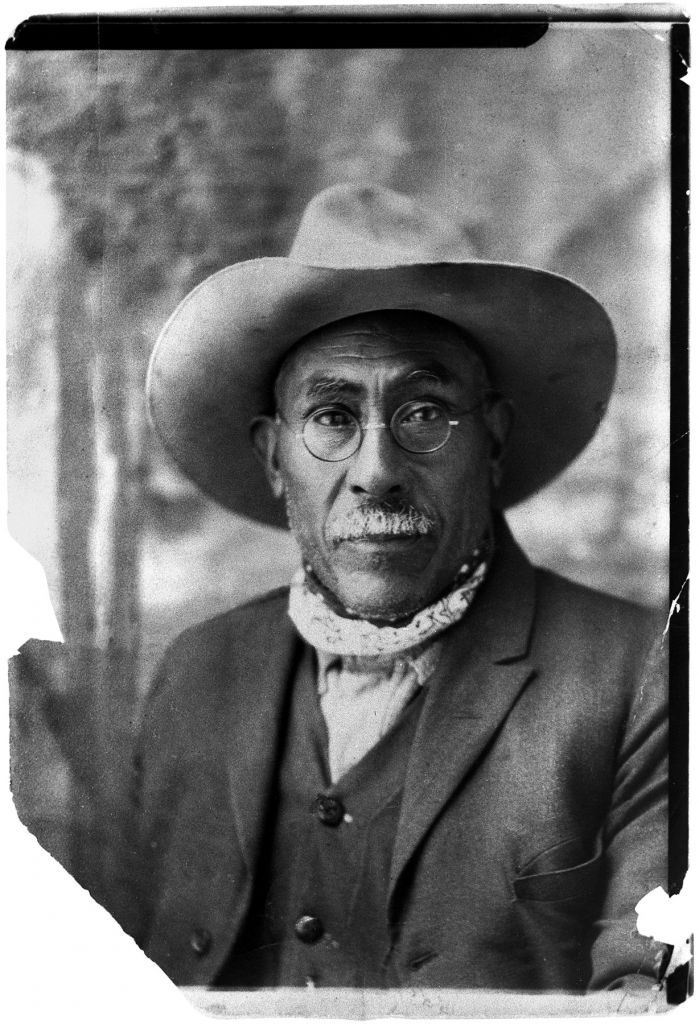

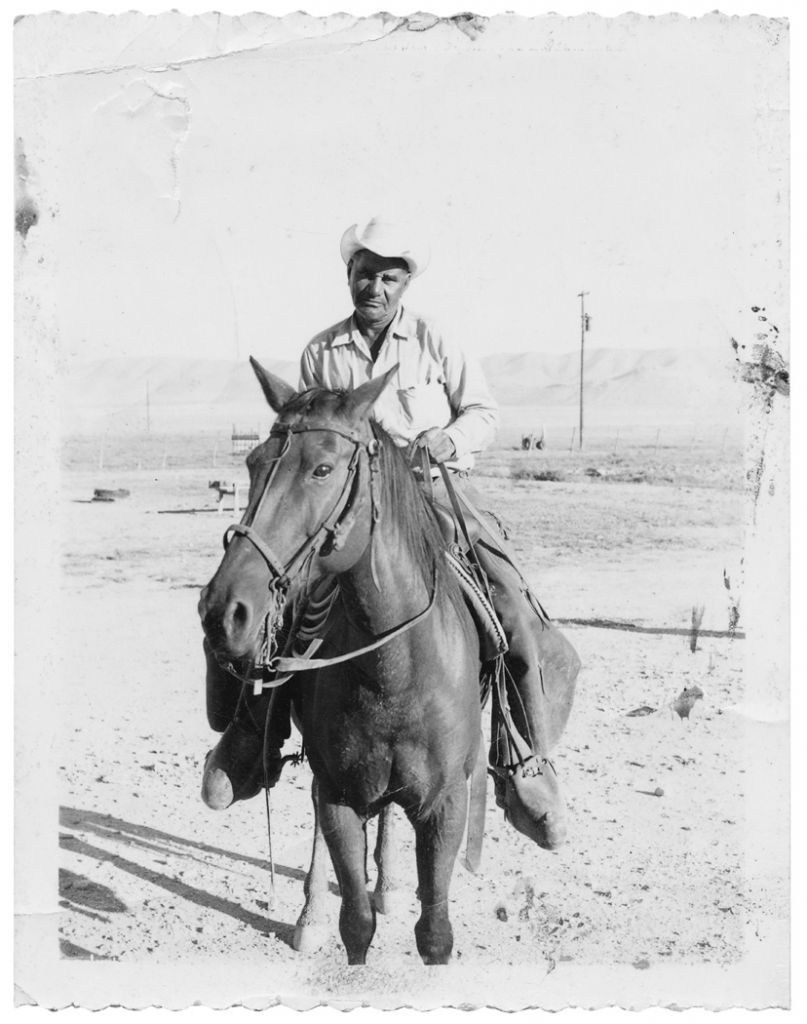

Blas Payne, 1901-1990, son of John Payne, lived for many years at the site of what was once Camp Peña Colorado, an outpost of Fort Davis where Black Seminole Indian Scouts were stationed. Blas’s mother was Refugia Vasquez, known as “Cuca” who was an ex-slave and lived for over 105 years. Blas managed the Combs Ranch after his father died, for over 45 years and was respected as one of the best cowboys and horse-handlers in the Big Bend.

Blas Payne was known for his wit and humor, and his horse-handling and animal husbandry skills.

Bibliography

- AnneJo Perry Wedin Papers, Archives of the Big Bend, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas

- General Photographs Collection, Archives of the Big Bend, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas

- Perry, AnneJo. The Magnificent Marathon Basin. 1989. Eakin Press: Texas

- Holley, Joe. The Saga of Blas Payne, a Big Bend Cowboy Legend. Houston Chronicle. July 5, 2014.

- Krapf, Kellie A. and Largent, Floyd B. Jr. The Black Seminole Scouts: Soldiers Who Deserve High Praise. Persimmon Hill: Winter 1996.

- Gray, Trace-Etienne. “Black Seminole Indians”. TSHA: Handbook of Texas Online. Accessed February 1, 2019.

- Tate, Michael C. Back Seminole Scouts. TSHA: Handbook of Texas Online. Accessed February 1, 2019.